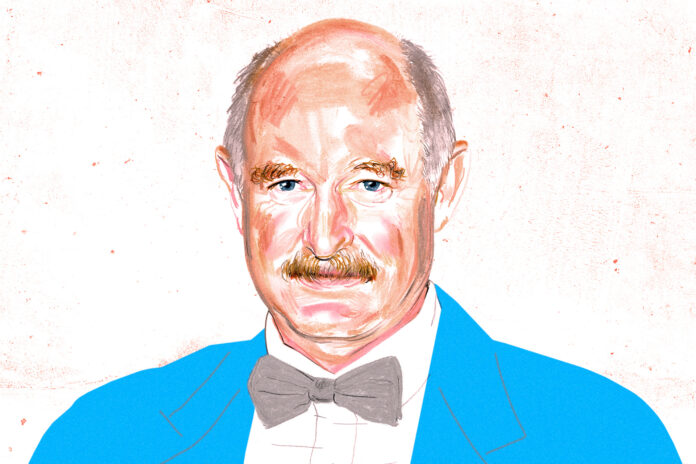

When Rafael Yuste was a teenager growing up in Madrid in the 1970s, he had two great loves: the brain and the piano.

At age 15, he began working in a clinical laboratory run by his mother, where he was tasked with looking through a microscope and counting blood cells. He read the autobiography of 19th-century Spanish neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, in which the famous researcher spent nights in his basement with tissue samples, unraveling the mysteries of the brain as part of a grand quest to help humanity. The romantic depiction of a scientist’s life captures the imagination of young Yeast.

And then there was the music. Yuste played the piano and dreamed of becoming a great composer. So he signed up to study at the Royal Conservatory of Music. In parallel, he entered medical school.

He didn’t realize it then, but his two great loves would merge: he became a professional pianist – the piano is without the brain.

“Imagine that the brain is like a piano keyboard,” Yuste, now a neuroscientist at Columbia University, told me. “Each neuron is a key. And with light, we can play the keys.”

A method called Yuste is mentioned Optogeneticswhich he used on mice as part of an effort to understand how the brain generates perception and behavior. It makes a genetic change in the neurons, usually by infecting them with a virus, that makes them responsive to light. Then you can Use a laser to activate specific neurons In the visual cortex of the mouse brain. This allows the mouse to see things that aren’t actually there.

“When you activate a neuron with light and make it fire, that’s what we call ‘playing the piano,'” Yust told me. The phrase is now used as shorthand for the technique in scientific papers. When he pioneered it on mice a decade ago, he was amazed at how easily he could manipulate their visual perception. Whenever he artificially created images in their brains, the rats behaved as if the images were real.

“From a science point of view, it was fantastic, because we finally got into the brain—we cracked the code that the neurons were using,” he described. “During the day, we were very happy, congratulating each other in the lab. But I did not sleep at night.”

It was his first idea that he would one day be involved in making laws to prevent people from manipulating each other’s brains. He created the mouse version of it movie the beginning. And mice are mammals, with brains similar to our own. How long, he thought, until someone tries to enter the human brain?

“That was my Oppenheimer moment,” Yuste said, referring to the nuclear physicist who helped design the atomic bomb. “You know like in the movie, when Oppenheimer looks at the first nuclear reactor and says, ‘Holy moly, look what I’ve done,’ and you see his face go sour?”

In fact, Yust had a strange connection with Oppenheimer. Every morning, when the neuroscientist walked into his office on Columbia’s Morningside campus, he looked out the window. It looked at a historical part of the Manhattan Project: very building Where American scientists first prototyped nuclear reactors during World War II.

The view from his window awakens his own horror at what he has created – and fuels his determination to make sure the technology is properly regulated. After all, many were among the physicists who built the bomb Those who will go to lobby The US government and the United Nations to regulate nuclear energy. This led to 1957 establishment The International Atomic Energy Agency, which still helps keep countries from blowing each other up with nuclear bombs.

So, in 2017, Yuste gather About 30 experts will meet in Columbia, where they’ll spend the day unpacking the ethics of neurotechnology. He wasn’t worried about forms of it that need to be surgically implanted in the brain — those are medical devices, subject to federal regulations. But he worries that unregulated, non-invasive neurotech is increasingly coming to the consumer market, which records your neural data (like the Muse meditation headband, which uses EEG sensors to read your brain activity patterns). So it could be sale Used to find out if someone has a condition like epilepsy, even if they don’t want to disclose that information to third parties. Perhaps it could one day be used to identify individuals against their will.

And as Yust’s mouse experiments have shown, it’s not just emotional privacy that’s at stake; There is also the risk of someone using neurotechnology to directly manipulate our minds. While some neurotechnologies aim only to “read” what’s happening in your brain, others also aim to “write” the brain—that is, to directly change what your neurons are doing.

The group of experts convened by Yuste, now known as the Morningside Group, was published A the nature paper Four policy recommendations later that year, which were later expanded to five in Yuste. Think of them as the new human rights for the age of neurotechnology:

- emotional privacy: You should have the right to segregate your brain data so that it is not stored or sold without your permission.

- personal identity: You should have the right to be protected from changes to your feelings that you did not approve of.

- free will: You should retain ultimate control over your decision-making, without the unknown manipulation of neurotechnology.

- Fair access to mental growth: When it comes to mental enhancement, everyone should enjoy equality of access, so that neurotechnology doesn’t just benefit the rich.

- Protection against bias: Neurotechnology algorithms should be designed in a way that does not maintain bias against certain groups.

But Yuste was not content with just writing academic papers. “I’m a person of action,” he told me. “Just talking about a problem is not enough. You have to do something about it.” So he teamed up with Jared Genser, an international human rights lawyer who has represented clients such as Nobel Peace Prize laureates Desmond Tutu and Aung San Suu Kyi. Together, Yuste and Genser created Neurorights Foundation To advocate for the cause.

They soon noticed a big win. In 2021, after helping draft a constitutional amendment in Yuste with a close friend who was a Chilean senator. become The first nation to include the right to emotional privacy and the right to free will in its national constitution. Then the state of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil pass own constitutional amendment (including a federal constitutional amendment in the works). Mexico, UruguayColombia and Argentina are considering similar legislation.

For the United States, Yuste has advocated for the neuroright in the White House and Congress. He knows, though, that change at the federal level will be a tough mountain to climb. Meanwhile, there’s a simple approach: States that already have comprehensive privacy laws can amend them to cover emotional privacy.

With Yuste’s help, Colorado became the first US state to take that path, passing new legislation this year that amends its privacy laws to include neural data. California followed suit, passing legislation that brought brain data into the category of “sensitive personal information.”

If U.S. federal law is followed, the neural data would fall under HIPAA’s protections, which Yuste said would virtually prevent all the potential privacy violations he worries about. Another possibility is to recognize all neurotech devices as medical devices so that they must be approved by the FDA.

Ultimately, preventing a company from collecting brain data in one state or even one country is of limited use if it can do so elsewhere. The holy grail would be international law.

So, Yuste has spoken to the United Nations, with some modest success so far. After meeting with Yust, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres mentioned neurotechnology in his 2021 Future of Humanity report, “Our common agenda“

Among his most ambitious dreams, Yuste wants a new global treaty on neurorights and a new international organization to make countries abide by it. He envisions the creation of something like the International Atomic Energy Agency, but for brains. It’s a bold vision from a modern-day Oppenheimer.