A suggestion column o your mileage may varyGiving you a new framework for thinking through your moral dilemmas and philosophical questions. This is obsolete The column is based on value pluralism – the idea that we each have multiple values that are equally valid but that often conflict with each other. Here’s a Vox reader question, edited for brevity and clarity.

I feel it is my duty to help people who are much poorer than me, and I give 10 percent of my salary to charities that are effective in preventing early deaths due to poverty. I live in a city with a lot of visible homelessness and frequent requests for money. My brain says this is not an effective way to help people; The people asking may not be the neediest of the homeless in my city, and the ones I send malaria bednets and pills to are even more needy. At the same time, I feel callous to simply ignore all these requests. What should I do?

The favorite optimizer would be,

Nine times out of ten, when someone has a moral dilemma, I think it’s because some of their core values conflict with each other. But you are the tenth case. I say this because I don’t actually believe your question represents a battle royale between two different values. I think there’s a core value – helping people – and a strategy masquerading as a value.

That strategy is optimization. I can tell from your phrasing that you are really into it. You don’t just want to help people – you want to help people as effectively as possible. Since extreme poverty is concentrated in developing countries, and since far more of your dollars go there than in your own country, your optimizing impulse tells you to send your charitable giving abroad.

Optimization began as a technique for solving specific math problems, but our society has elevated it to the status of a value — arguably one of the dominant values in the Western world. It has been growing since the 1700s, when utilitarian thinkers seeded the idea that both economics and ethics should focus on maximizing utility (money, happiness, or satisfaction): just calculate how much utility each action will produce, and choose one. which produces the maximum

You can see this logic everywhere in modern life — from work cultureWith an emphasis on productivity hacks and agile workflows, from Wellness cultureWith an emphasis on achieving perfect health and optimal sleep. The mandate is “Live your best life!” Turbocharged by Silicon Valley, which urges us to measure every aspect of ourselves with Fitbits, Apple Watches, and Oura Rings, because the more data you have on your body’s mechanical functions, the more you can optimize the machine.

Have a question you’d like me to answer in your next Mileage Very column?

Feel free to email me sigal.samuel@vox.com or Fill out this anonymous form! Newsletter subscribers will receive my column before anyone else and their questions will be prioritized for future editions. Sign up here!

Optimization certainly has its place, including in the charity world. Some charities are more effective than others trying to achieve the same goals. All things being equal, we don’t want to blow all our money wildly on ineffective ones. Effective philanthropy, members of utilitarian-flavored social movements that aim to do the best possible, observe that the most effective charities out there actually produce 100 times more benefits Compared to the average ones. why no Get the biggest bang for your buck?

The problem is that we have stretched the optimization beyond its optimal limits. We try to apply this to everything. But not every domain of life can be optimized, at least not without compromising some of our values.

In your case, you’re trying to optimize how much you’re helping others, and you believe that means focusing on those most in need. But what is the definition of “necessary” needy? You might assume that financial need is the only type that counts, so you should focus on lifting everyone out of extreme poverty first and only then help people in less dire straits. But are you sure that only the level of brutal poverty is important?

Consider an insight from Jewish tradition. The ancient rabbis were very sensitive to the psychological needs of the poor and argued that these needs should also be taken into account. So they decreed that you don’t just give poor people enough money to live on – they need to have more than that so they can give to others themselves. As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks wrote“On the face of it, the rule is absurd. Why give X enough money so that he can pay Y? Giving Y directly is more logical and efficient. But what the rabbis understood was that charity is an essential part of human dignity.”

The rabbis also thought that people who were well-off but who fell into poverty were especially likely to feel a sense of shame. So they suggest helping these people save face by offering them not just the necessities, but — when possible — some of the niceties that dominated their former lifestyles. in the TalmudWe hear of a rabbi who gave a newly poor man a fancy meal, and another who served as the man’s servant for a day! Clearly, the ancient rabbis did not only aim to alleviate poverty. They were also alleviating the shame that might accompany it.

The point is that there are many ways to help people and, because they are so different, they do not lend themselves to direct comparison. Comparing poverty and shame is comparing apples to oranges; One can be measured in dollars, but the other cannot. Similarly, how can you ever hope to compare malaria prevention with depression relief? Saving lives vs improving them? Or saving a child’s life versus saving an adult’s life?

Yet if you want to optimize, you need to be able to run an apples-to-apples comparison — to calculate how well different things do in a single currency, so you can choose the best option. But since helping people can’t be reduced to one thing—it’s many irreplaceable things, and how to rank them depends on each person’s subjective philosophical assumptions—trying to optimize in this domain means you have to artificially simplify the problem. You have to pretend there are no such things as oranges, only apples.

And when you try to do that, an unfortunate thing happens. You’ll run past all the homeless people in your town and, as you write, you’ll “feel callous to ignore all these pleas.” Ignoring these people comes at a price, not just for them, but for you. This has a detrimental effect on your moral conscience, which feels motivated to help but is being asked not to.

This story first appeared in the Future Perfect Newsletter.

Sign up here to explore the big, complex problems facing the world and the most effective ways to solve them Sent twice a week.

even Some leaders of effective philanthropy And the adjacent rationalist community recognizes this as a problem and advises people not to close that part of themselves. Rationalist Eliezer Yudkowsky, for example, says that it’s okay to donate some money to causes that make us feel warm and fuzzy but that don’t create maximum utility. His advice is “Buy Fuzzy and Utilon separately” — meaning, dedicate one pot of money to pets and another (much larger) pot of money to the most affordable charity. You can get your warm fuzzies on by volunteering at a soup kitchen, she says, and “let it be.” valid by your other attempts to purchase Utilon.”

I would recommend diversifying your giving portfolio, but this no Because I think you need to “validate” the warm fuzziness. Instead, it’s because of another quality: integrity.

While the twentieth-century British philosopher and critic of utilitarianism Bernard Williams Speaking of integrity, he meant it in the literal sense of the word, relating to the wholeness of a person (think of related words like “unification”). He argued that moral agency does not sit in a contextless vacuum—it is always the agency of certain individuals and that we as certain individuals have specific commitments.

For example, a mother has a commitment to ensure the well-being of her child, over and above her general desire for the well-being of all children everywhere. Utilitarianism says that she should consider everyone’s well-being equally, with no special treatment for her own child — but Williams says that’s an absurd claim. It cuts him off from a core part of himself, shreds him, destroys his wholeness – his integrity.

You seem to experience this when you encounter a person experiencing homelessness and ignore them. Ignoring them makes you feel bad because it cuts you off from the part of you that is affected by this person’s suffering – that Looking orange But it is said that there are only apples. That core part of you is no less valuable than the optimizing part, which you compare to your “brain”. It is neither silly nor absurd. It’s the part that cares deeply about helping people, and without it, the optimizing part would have nothing to optimize for!

So instead of trying to override it, I would encourage you to honor your desire to help in all its fullness. You won’t be able to run a direct apples-to-apples comparison, but that’s okay. Different types of aid are useful in their own ways and you can divide your budget between them, although there is no perfect formula to spit out the “optimal” allocation.

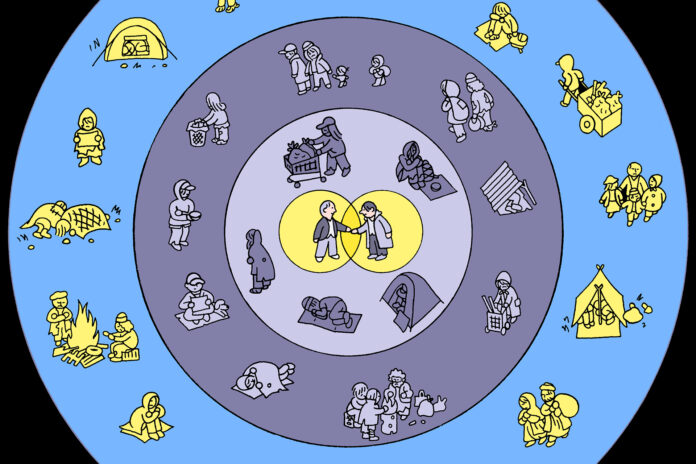

Diversifying your giving portfolio might look something like this. You carry a small amount of cash or gift cards, which you hand out to homeless people you encounter directly. You set aside a large amount to donate to a local or national charity with a strong track record. And you donate another amount to a very effective charity abroad.

You may feel frustrated that there is no universal mathematical formula that can tell you the best thing to do. If so, I get it. I also want the magic formula! But I know that desire is different from the original value here. Don’t let optimization eat away at your beloved value.

Bonus: What I’m Reading

- I recently read The ultimate illusionA book by mathematician Coco Crum that traces the roots of optimization’s overreach. As he says, “Over the past century, optimization has occupied an impressive amount of cognitive land.”

- When torn between competing moral theories, does it make sense to diversify your donations in proportion to how much you believe in each theory? Some philosophers argue against this view, but Michael Plant and co-authors defend it This is a new paper.

- This is a wonderfully written article Anthropologist Manveer Singh introduced me to the term “collaborating without seeing” (or, as this is a New Yorker article, “collaborating without seeing”). This “tendency to deliberately ignore costs and benefits when helping others” — to help without counting what you will gain from the altruistic act — “is a key feature of both romantic love and ethical behavior.” When we help in this way, people trust us more.