This is the first in a series of stories on how factory farming shapes America. You can visit Vox’s Future Perfect section for future installments and more coverage of Big Ag. This series is supported by Animal Charity Evaluators, which received a grant from Builders Initiative.

In early 2023, Marielle Williamson emailed her Los Angeles high school principal requesting permission to protest milk.

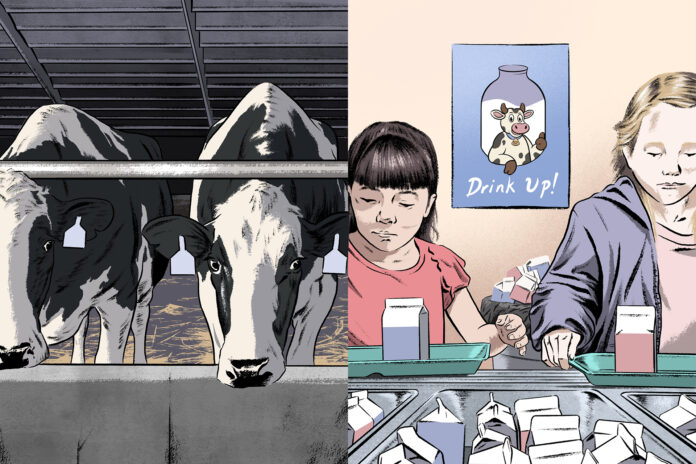

A senior and president of the school’s Animal Awareness Club, Williamson wanted to set up a table outside the school cafeteria to distribute literature about inhumane conditions on dairy farms and the pollution they spew — and promote alternatives, like soy milk. It would be counterprogramming to the Got Milk? advertisements aired during the school’s morning announcements and plastered across the school’s hallways.

Williamson eventually got the green light from her principal, but with one confounding stipulation: She’d also have to promote the benefits of cow’s milk.

The school’s demand stemmed from a US Department of Agriculture (USDA) policy that states schools “must not directly or indirectly restrict the sale or marketing of fluid milk.” Doing so would violate the rules of its participation in the National School Lunch Program, which all public — and many private — schools heavily rely on to subsidize their meals, and could result in fines and other corrective actions.

The policy “goes to show the stranglehold that the dairy industry has over LAUSD [Los Angeles Unified School District], over schools that participate in the National School Lunch Program,” Williamson told me.“My principal is a great guy, but it was the policy that he just had to follow.”

Rather than acquiesce, Williamson protested the policy. Working with the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), a plant-based nutrition advocacy group, she sued the USDA, the Los Angeles Unified School District, and her school’s administrators, arguing her right to free speech had been violated.

Months later, the school district settled the lawsuit, affirming students’ right to criticize dairy. The district also accepted a donation from PCRM to be used to purchase soy milk for students who want it, free of charge. (The USDA did not join the settlement and has sought to dismiss the lawsuit.)

Dairy’s stranglehold on school food began some 80 years ago and has only tightened since. It was built on the outdated idea that cow’s milk is essential for children’s health — an idea that has had immense staying power due to a vast and deep-pocketed marketing, lobbying, and research machine. That misconception has resulted in policies like the one Williamson was up against, and the nationwide requirement that milk must at least be offered, and in many schools must be served, to every student at every school meal.

In recent decades, though, milk consumption has rapidly declined while nutritionists have increasingly come to question milk essentialism. Most people of color — along with one-fifth of white people — can’t even properly digest it, and it’s not necessary to the maintenance of a healthy diet.

And it’s an unsustainable product, both environmentally and financially. In 2015, according to one estimate, a staggering 71 percent of dairy farmers’ revenue was dependent on government support.

The school cafeteria is the most important arena in which the debate around milk has played out. The National School Lunch Program accounts for a significant portion of milk sales and helps kids acquire a taste for the stuff — and the notion of its necessity — at an early age.

Williamson and others who want to reduce schools’ reliance on milk are fighting against decades of indoctrination. But the resistance she faced when proposing a simple protest shows how difficult it will be to break dairy’s grip over the government — and the rest of us.

A superfood is born

The story of milk as a children’s superfood begins in the early 1700s with a man in the London suburbs named Dr. Taylor, who claimed an all-milk diet had cured his and many of his patients’ epilepsy. Taylor’s diet never took off, but it did inspire another doctor: George Cheyne, a Scottish physician, writer, and religious mystic.

Cheyne, a vegetarian who considered cow’s milk as a kind of middle ground between meat and vegetables, recommended an adaptation of Taylor’s all-milk diet that included vegetables but no meat.

According to Anne Mendelson, author of Spoiled: The Myth of Milk as Superfood, Cheyne’s dietary regimen was “one of modern England’s first celebrity diets.” After he died, his belief in an “Edenic, blameless diet,” as Mendelson put it, was picked up by other physicians and applied in a new context: Humble cow’s milk came to be considered nature’s perfect food for children.

Why I wrote this

Our food environment — what we’re served at school, in restaurants, and on grocery store shelves — is shaped by federal policy. Through my years of reporting on animal agriculture, it became evident that dairy, and especially milk, has been foisted on us more than any other food, and often against common sense. That quickly became clear after tracing the history and marketing of milk since the 1700s.

“It acquired and never has lost a uniquely exalted status as a life-giving proxy for mother’s milk, a concept not closely related to any nutritional reality,” Mendelson wrote. It’s an aberration she considers — along with the belief that milk is an incomparably healthy food for adults — to be “probably one of the biggest mistakes in the history of modern nutrition.” (And to state the obvious but taken-for-granted fact of milk consumption, humans are generally the only species that drinks the milk of another species, and drinks milk past infancy; cow’s milk is designed for calves and therefore has a different nutrient profile from human breast milk.)

As demand grew, the US government took perhaps the most consequential actions in the history of milk: In 1862, it established the Department of Agriculture along with a slew of state and university agricultural research centers across the country.

The massive research effort was, and remains today, devoted to maximizing agricultural output from crops and livestock, including dairy cows. Eventually, crop scientists figured out how to preserve hay and other grasses to feed cows during the winter, and milk production moved from a seasonal to a year-round model.

As America’s milk sector industrialized and output kicked into high gear, creating enormous surpluses, the dairy industry found its biggest and most enduring base: schoolchildren.

How milk took over the market — and the school cafeteria

In 1946, Congress established the National School Lunch Program to subsidize school meals. The legislation had a dual purpose: to ensure ample calories and nutrition for children and to offload agricultural surpluses, including milk. Schools were required to serve students one cup of whole milk at every meal. The law was a win-win for industry: Overnight, it locked in arguably its biggest customer, and shedding some of its overproduction in turn raised prices for dairy producers.

Milk consumption peaked around this time and steadily fell in the following decades due to a confluence of factors, including the discovery of lactose intolerance among many people of color in the 1960s and the growing popularity of soda, juice beverages, bottled water, and, eventually, plant-based milks over the following decades.

In the 1970s and ’80s, there were also growing concerns over dietary saturated fat. The USDA — a longtime friend to industry — and the US Department of Health and Human Services dealt a painful blow to dairy’s superstar nutrition status when the first-ever federal dietary guidelines were published in 1980, in which experts advised Americans to eat dairy and other animal fats in moderation.

“The meat, milk, and egg people thought the USDA had stabbed them in the back,” Mark Hegsted, who oversaw human nutrition for the USDA at the time, said later.

“They thought or assumed the primary obligation of the USDA was to protect and promote agriculture,” not optimal human nutrition, Hegsted, who had begun to question milk’s nutritional value in the 1950s, later said. He was assigned to a new position the following year.

But things turned around for Big Dairy a few years later in what became the most consequential law for milk in recent decades.

In 1983, Congress passed legislation to create the National Dairy Promotion & Research Board, a semi-governmental organization overseen by the USDA with the singular goal of increasing dairy sales. In 1990, it created an equivalent entity just for milk. Both are funded by skimming off 15 to 20 cents from every 100 pounds of milk produced, which generates over $400 million annually for a sprawling web of advertising and research organizations. (The USDA has created such entities for over 20 agricultural products, but dairy is far and away the largest.)

That pot of money brought us the Got Milk? campaign of the 1990s and early 2000s, considered one of the greatest advertising campaigns in history, from the national Milk Processor Education Program, or MilkPEP, and the California Milk Processor Board. But it couldn’t stanch the bleeding. Milk consumption continued to decline and hit a new low in 2022. Over the decades, intensive consolidation in the dairy industry has driven tens of thousands of farmers out of business.

School cafeterias have been essential to helping milk hang on; today, schools alone purchase around 8 percent of the US fluid milk supply.

In recent years, the cool, casual Got Milk? slogan has been replaced with the nagging, anxiety-tinged Gonna Need Milk, which has been targeted squarely at Gen Z. The campaign has featured amateur athletes, Olympians, and e-sports stars. It’s even paid actress Aubrey Plaza to make fun of plant-based milks and star YouTuber MrBeast to talk up dairy sustainability. (Milk’s per-pound carbon footprint has gone down in recent decades, but plant-based milks are still vastly better for the environment.)

MilkPEP didn’t respond to an interview request for this story.

The quasi-governmental dairy promotion board, Dairy Management, Inc., has embedded dairy scientists in fast food companies to formulate new, extra-cheesy menu items, like Taco Bell’s grilled cheese burrito, which contains 10 times as much cheese as a typical taco, and has partnered with Domino’s to produce a specialty product for school lunch programs. While milk sales have crashed in recent decades, these efforts have helped cheese sales soar.

Dairy can certainly be part of a healthy diet. But incessant marketing and proactive initiatives to jam as much milk and cheese into schools and fast food restaurants as possible conflicts with the federal dietary guidelines, which recommend limiting sodium, saturated fat, and added sugar.

Dairy Management, Inc. did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

The USDA’s “nutrition and marketing missions and goals do not conflict,” an agency spokesperson said in an email. “USDA does not have a supporting role, but rather an oversight role in industry marketing efforts.”

“The nutrition community has bought that dairy foods are semi-essential without much critical thinking,” said Marion Nestle, a New York University nutrition professor and renowned author of numerous books on the food industry’s influence on nutrition research and policy.

That’s begun to change, with some nutrition leaders challenging industry’s efforts to foist dairy onto consumers and kids.

Questioning milk essentialism

Despite the lack of evidence — and the fact that so many Americans have difficulty digesting milk — the USDA, the dairy industry, and many in the nutrition community continue to repeat the narrative that we must consume copious amounts of dairy, citing its high calcium levels, to build strong bones and prevent fractures later in life.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, dairy industry representatives even warned of a “calcium crisis” and pushed a “3-a-day” servings advertising campaign. Eventually, they got their wish: In 2005, the government upped its recommended daily servings of dairy products from two or three, depending on the age, to three for everyone.

But the amount of calcium we need is in dispute, and it doesn’t need to come from dairy.

“Yes, you need calcium for healthy bones, there’s no question about that,” said Erica Kenney, an assistant professor of public health nutrition at Harvard University. But there’s a mismatch, Kenney said, between the accepted wisdom on milk, calcium, and bone density, and what the scientific literature says.

Kenney pointed to a 2020 paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine simply titled “Milk and Health,” co-authored by two of her Harvard colleagues: preeminent nutrition scholar and longtime dairy skeptic Walter Willett and pediatrics professor David Ludwig.

In the paper, they sort through decades of research to conclude that high milk consumption during adolescence and adulthood doesn’t reduce the risk of hip fracture later in life.

“Low dairy consumption is clearly compatible with low rates of hip fracture,” the authors write. High milk intake during adolescence may even “contribute to the high incidence of fractures.” That’s evident in parts of Europe, where some of the most milk-hungry countries have the highest rates of hip fractures. Meanwhile, much of Asia experiences low rates of hip fractures and consumes little milk.

Calcium needs are not universal and can be influenced by several dietary factors. For example, high Vitamin D intake helps the body absorb calcium, while high protein intake excretes calcium — what’s known as the “calcium paradox,” which could help to explain those differences between Europe and Asia.

It’s worth cautioning that much of the research on calcium, bone health, and fracture risk is correlative, not causal — as is the case with so much nutrition science. But the authors believe US government calcium recommendations — which are based on studies with “serious limitations” — are too high. For all age ranges, US recommendations are much higher than the United Kingdom’s, and for some age ranges, they’re higher than those of the World Health Organization.

However much calcium one requires, Kenney noted, it doesn’t need to come from milk. Other calcium-rich foods include nuts, beans, lentils, tofu, sardines, seeds, and dark leafy greens. Calcium is just one of several factors that determines bone health; exercising, avoiding smoking, minimizing alcohol consumption, and getting plenty of vitamin D can help build strong bones, too.

Overall, dairy’s impact on health outcomes is mixed. Its consumption is correlated with greater risk of some cancers, especially prostate cancer, but is inversely associated with the risk of colorectal cancer. In one large, multi-decade study, dairy consumption was associated with lower mortality than processed red meat and eggs but significantly higher mortality than plant-based protein.

Willett has said milk is optional — as has the American Medical Association — so long as you’re following a high-quality diet, and Harvard’s Healthy Eating Plate limits dairy to one to two servings per day. The three servings per day recommendation, in Willett and Ludwig’s view, is not scientifically justified.

“The current edition of the Dietary Guidelines, the 2020-2025 edition, is based on the preponderance of current scientific and medical knowledge,” a USDA spokesperson said in an email, adding that people can meet dietary recommendations with fortified soy products.

The guidelines’ recommendation may also stem from an inherent conflict in the USDA’s role. “The USDA has a dual mission of providing healthy food to children and supporting American farmers,” the agency’s website says.

“Those things are not always necessarily going to be perfectly aligned,” Kenney said.

Ending the USDA’s milk-crazed era

Marielle Williamson’s inability to simply criticize dairy at school shed light on the industry’s influence in school cafeterias. But she’s not alone in facing absurd USDA rules that govern school food.

About a decade ago, it came to USDA officials’ attention that some schools in Oklahoma and Kansas had hung posters in the cafeteria informing students that they could choose water instead of the milk that was offered to them.

Kids throw away an astonishing 41 percent of milk in schools, according to USDA research, so the signs could be interpreted as an innocuous means of reducing food waste. But the dairy industry wouldn’t tolerate it.

According to documents obtained by PCRM through a Freedom of Information Act request, in 2016 an executive from the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA) complained to the USDA undersecretary that its members “have reported declining milk consumption in school districts that are encouraging students to take free bottled water instead of milk.”

“It’s appropriate for schools to offer water — they should be offering water to students, but certainly not in a way that conflicts with offering milk,” Matt Herrick, a spokesperson for IDFA, told me.

In 2018, the USDA sent a “clarification” memo to every child nutrition state director, warning them that water offered to students “should not be made available in any manner that interferes with selection of components of the reimbursable meal, including low-fat or fat-free milk.” The emails obtained through FOIA show that part of the memo was drafted by two large dairy companies — Prairie Farms and a company it owns a majority stake in and manages, Hiland Dairy — which had also complained to the USDA about the matter. Internally, the USDA committed to “increase monitoring of the beverage marketing practices across the nation.”

“Regarding the posters mentioned, our primary concern was to clarify the nutritional options available to students,” a Hiland Dairy spokesperson wrote in an email. “Providing accurate information about milk’s benefits and other hydration options like water helps students and their families make informed choices. Our goal has always been to support policies that promote children’s health, not to overreach or diminish other valuable components of their diet.”

Prairie Farms didn’t respond to an interview request for this story. The USDA did not respond to a question relating to the 2018 memo in time for publication.

So, what would a more reasoned, evidence-based milk policy look like? For starters, schools shouldn’t be required to serve it. It also shouldn’t be served at every meal. And when it is served, students should have a choice about whether to take it, said Nestle. Right now, around 20 percent of schools require elementary and middle school students to take milk every day.

A USDA spokesperson said that the agency encourages schools to offer, rather than mandatorily serve, milk to “reduce food waste and give students more choices with their meals.”

Kenney agreed with Nestle that milk should always be optional, especially because lactose intolerance is common among people of color, who now make up a majority of public school attendees. Milk is also the most common allergen among children.

“A lot of kids of color are having milk served to them and they can’t really eat it or digest it comfortably and without getting sick,” Kenney said. The ADD SOY Act, introduced in the US House and Senate, would expand access to soy milk in schools; currently, students face a burdensome process to get it — another issue Williamson wanted to raise awareness about in her school.

“USDA recognizes that the structure in place can be burdensome for families who wish to request a substitution or modification for fluid milk, whether for non-disability or disability reasons,” an agency spokesperson said. (The USDA said that lactose intolerance may be considered a disability.)

“USDA has acted within its authority to make the process less burdensome by broadening the scope of health professionals who can provide documentation to support a child’s need for a reasonable modification for a disability … USDA does not have the authority to require that milk substitutes be made available for all students nor to provide additional funding to encourage schools to do so. This would require Congressional action.”

Many nutrition groups, medical experts, and parents also want to see further limits or an outright ban on sugary flavored milks, like chocolate and strawberry milk, in schools. The USDA considered removing them from elementary and middle schools but recently declined to do so after dairy companies committed to reducing added sugar in flavored milk.

We would also be wise to rethink federal dietary guidelines on milk. One not-so-radical move would be to stop classifying dairy as its own food group, which Canada did in 2019.

On the US government’s MyPlate, a glass of milk is the beverage of choice, but in Canada, “the beverage of choice is water,” said Vasanti Malik, an assistant professor of nutrition at the University of Toronto. “Dairy still showing up to be recommended to be consumed on a daily basis [in the US], that’s where I think there’s some controversy or there’s not consensus.”

Historically, some of the experts who serve on the dietary guidelines committee have received funding from dairy companies and Dairy Management, Inc., the dairy advertising and research board overseen by the USDA. This remains the case for the committee advising the upcoming 2025-2030 guidelines and dairy nutrition research more broadly.

Big Dairy puts big dollars into making sure we’re bombarded with their products

Any reform efforts, whether in schools or the federal dietary guidelines, will be tough.

For some 160 years, industry and government have touted milk as a convenient, low-cost vessel for key nutrients, and they’re not wrong. But that talking point masks the reality that milk is only so convenient and affordable because the USDA, with taxpayer dollars, has made it so through intensive, sustained investments. At the same time, the industry has invested in government, giving millions of dollars to members of Congress annually.

It also invests in government personnel. Tom Vilsack first served as President Obama’s USDA secretary and left during the Trump administration to serve as president of the US Dairy Export Council — of which the USDA has oversight — until President Biden appointed him as USDA secretary. Karla Thieman, one of Vilsack’s chiefs of staff during his first term, lobbied for numerous dairy companies and associations in the years after she left the agency. Most of the lobbyists from the wealthiest dairy groups formerly worked in the federal government.

Companies and organizations that have large stakes in dairy also handsomely fund the nongovernmental but influential School Nutrition Association (SNA). Cargill, Dairy Farmers of America, Danone, Domino’s Pizza, Land O’Lakes, Kraft Heinz, and the National Dairy Council are all “patron” level donors, the highest level of support, which requires a $15,000 donation. The program is “designed to increase your organization’s interaction with school nutrition professionals,” according to the association. “As an SNA Patron, your company will enjoy greater exposure and access to school foodservice professionals nationwide.”

“Every company that sells to schools wants to sell more, and that’s really all you need to know,” said Nestle. “It’s really that simple. They will do whatever they can to get those products into the school, and they’ll do whatever they can to stop anything that stops them from getting those products into the schools.”